Blog by attorney Ken Harrell

I have just finished Andre Agassi’s autobiography, “Open.” Never was a book more aptly named. I can’t say that I ever gave a lot of thought to Agassi during the height of his career. If you grew up in Waverly, Virginia in the 1960s and 1970s, there were three sports – football, basketball, and baseball. I can honestly say that I don’t think I ever saw a real soccer ball until I went to college and I had equally little exposure to tennis and golf (which we considered to be sports for rich people). To the extent that I was aware of Agassi, I thought of him as something of a brash punk seeking the spotlight with ever-changing hair and fashion choices that made the traditional tennis world uneasy. After reading Agassi’s autobiography, I’m certainly a fan of the man he evolved into. It’s rare to read an autobiography that doesn’t have a sheen of pompous waxing, especially one by a celebrity (Agassi was married to Brooke Shields for a few years in the 1990s). On the contrary, Agassi bared his soul in this book. He spoke about how he came to hate tennis due to a controlling father who drove him relentlessly, and a stint at a tennis academy during his high school years. He spoke of his abject failure academically. He admitted many personal faults and lapses in judgment (including a stint of crystal meth use) that had him on the brink of squandering his immense talents during the height of his career. He also wrote about the frustration of being over-shadowed throughout his career by Pete Sampras, who defeated Agassi in a number of top tournament championships. Through it all, Agassi found a way to keep going – to keep re-making himself physically and to find some deeper sense of purpose in the game. He ended his career having won eight Grand Slam events and having spent several periods of time ranked as the number one tennis player in the world. Unquestionably, Andre Agassi was a “great” tennis player.

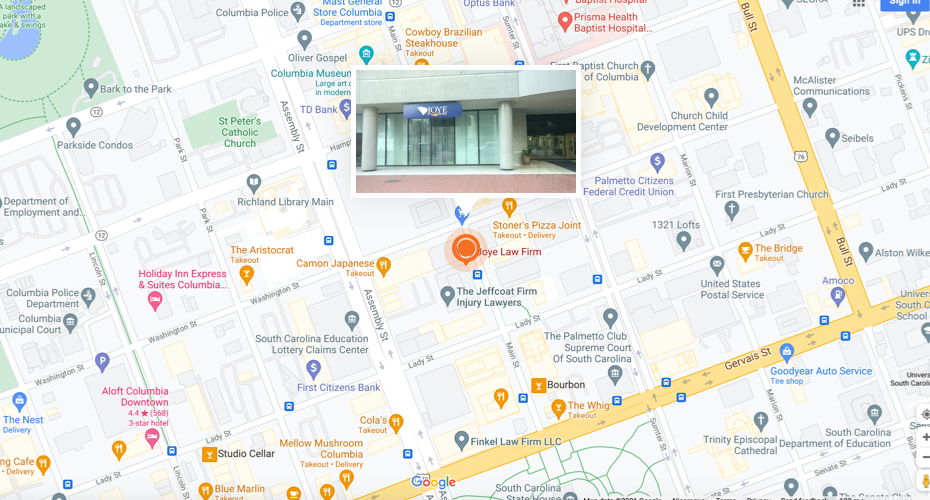

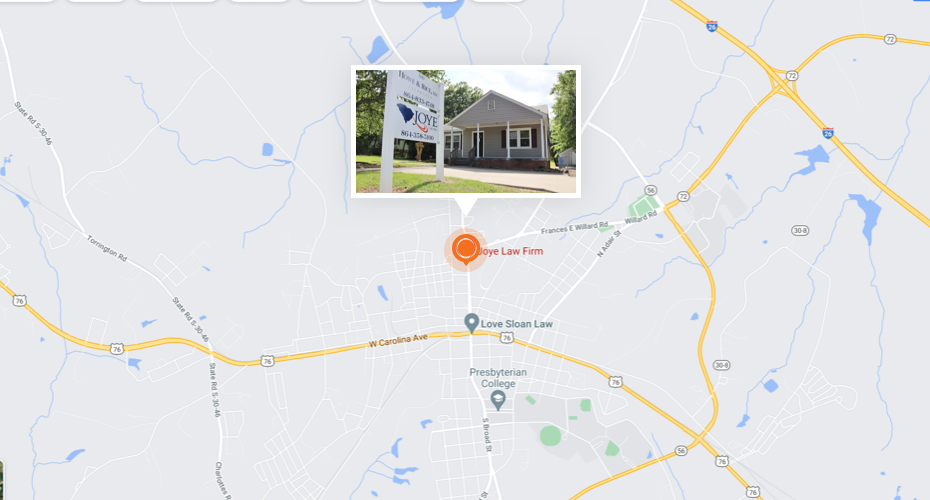

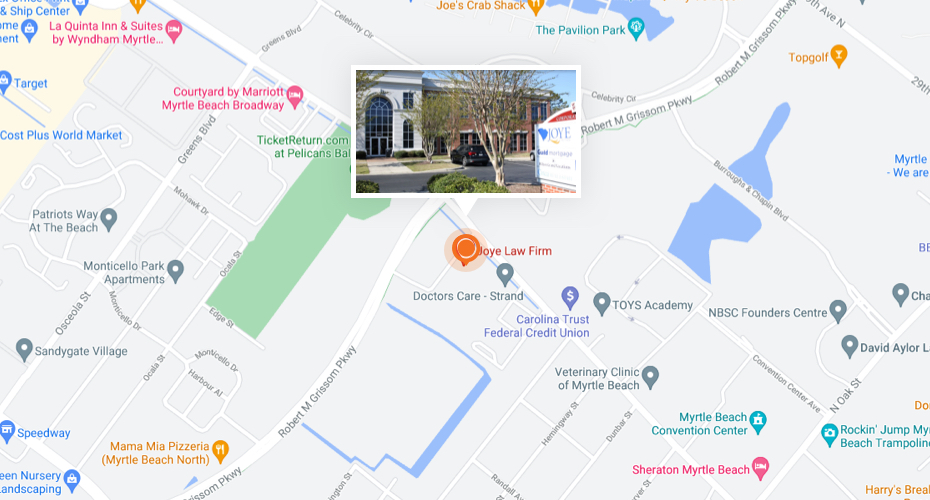

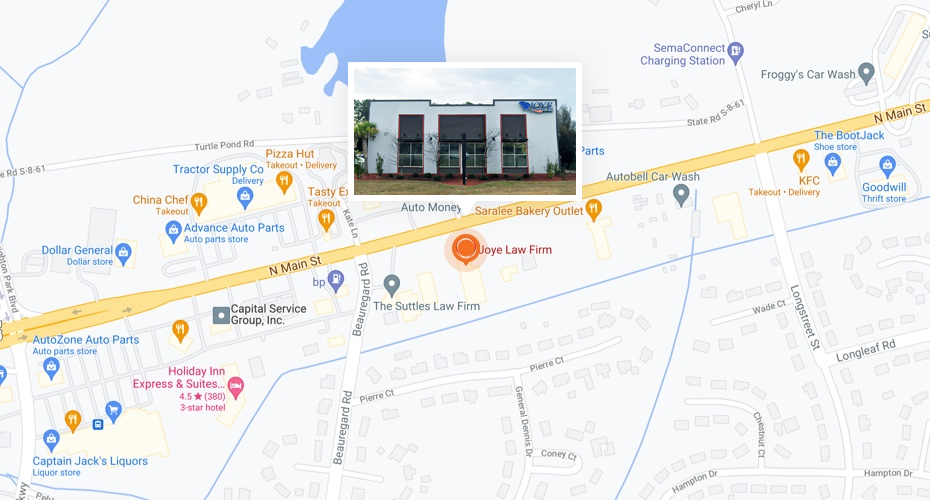

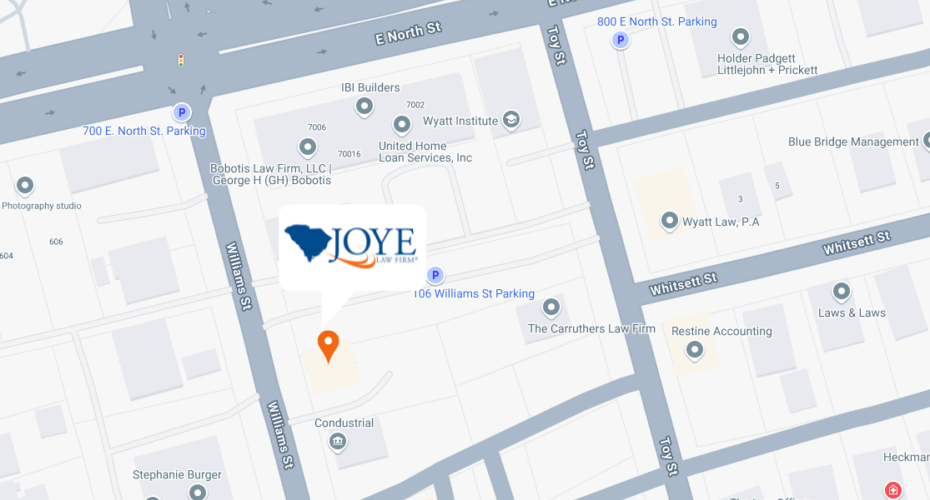

Agassi’s book left me thinking about the cost of greatness for all of us, in whatever endeavor we choose. Greatness is something that just about everyone claims to aspire to, although I’m convinced that only a very few people are truly committed to doing what it would take to be “great” in their field. As the managing partner of the Joye Law Firm, I’m very proud of the law firm we’ve built over the past 50 years. Much of the credit obviously goes to Reese Joye, our founder, and my law partner Mark’s father. Reese certainly laid the foundation for us to be successful. However, I’m also proud of the work Mark and I have done over the past 25 years to transform the firm into something far grander than Reese could have envisioned. None of this would have been possible if we didn’t have excellent lawyers and employees working for us. We have 18 lawyers at our law firm. I can undoubtedly say that all of them are very good at what they do. You can’t be a lawyer at this law firm without being good at your craft. There are also a few of our lawyers who are great at what they do. Just as with tennis greatness, there are a few traits that separate the great trial lawyers from the rest of the pack.

What Are Those Traits?

First, and foremost, is a work ethic that is hard to match. In his book “Outliers”, author Malcolm Gladwell opined that it takes 10,000 hours of practice for someone to master their craft. I would agree with that. Depending on how many hours a week someone is working, that’s four to five years of working. There has never been a new lawyer who had any idea of how to be a good lawyer on their first day of work. In my experience, it takes four to five years of experience before a lawyer truly has his or her sea legs under them to such an extent that they truly feel confident about doing their job. Fortunately, fledgling lawyers at our law firm are surrounded by a pack of lawyers who are willing to guide and teach them, and who are vested in seeing them succeed. However, Gladwell’s belief about the need to invest 10,000 hours is about how much time is needed to be competent in a craft, not to become great. The great lawyers have an engine that seems to run hot all the time. As I write this article on a Sunday afternoon in my office, I am reminded that the same two or three lawyers seem to be the ones I see working on weekends or late at night. There is a high cost for greatness. It is not for everyone.

Second is a level of competitiveness that borders on obsession.

Great trial lawyers love to win. However, what really drives them is that they hate to lose more than anything imaginable. All great trial lawyers lose cases. All great athletes lose games and matches. If a lawyer tells you he’s never lost a case, you’re talking to a lawyer who’s likely afraid of the courtroom (or who has spent his career cherry-picking the cases he tries on the rare occasions he enters a courtroom). The great trial lawyers not only learn from their defeats but they are sickened by them. They lose sleep, they lose appetite, and they go through a deep funk. When a lawyer is that deeply affected by his losses, his competitive drive will help spur him to greatness.

The third is courage.

I’ll brag about my law partner Mark here. Over the past year and a half, Mark has obtained two stellar verdicts in federal court – one for $6 million and the other for $12 million. Now that would be impressive in and of itself. However, what’s truly impressive is that prior to the trial of these two cases, Mark turned down a $3.5 million offer on the first case and an $8.7 million offer on the second. If you find a trial lawyer who has the courage (and the cajones) to turn down offers of $3.5 million and $8.7 million and then go out and get higher verdicts, you’ve found yourself a great trial lawyer. That’s a rare bird indeed.

Finally, great trial lawyers have a deeper sense of purpose that goes beyond a specific case and makes a lot of money.

Andre Agassi eventually found some purpose in tennis after marrying Steffi Graf (arguably the greatest women’s tennis player ever) and having children. More importantly, he was driven to succeed because he realized it would help him realize his goal of building a college preparatory academy in inner-city Las Vegas. (The Democracy Preparatory Academy at Agassi Campus will turn 20 next year.) The same commitment to a cause greater than a single case is a trait shared by many of the best trial lawyers. It starts by helping a client whose life has been catastrophically affected by a severe injury or by the death of a loved one start to rebuild their lives but it can often go beyond that. When Mark and I were young lawyers, we were fortunate to participate in a case that resulted in a $262.5 million verdict against Chrysler related to a defect with the latch on its minivan’s rear door. Mark’s closing argument, in that case, has been featured in books published on the art of a great closing argument. That verdict was eventually vacated by the Fourth Circuit Court of Appeals and the case then settled for a much lower amount. What the Fourth Circuit couldn’t vacate was the recall of these minivans by Chrysler to repair the defective latches. The verdict our law firm obtained played a role in saving lives – and there are countless other examples of civil trial results spurring safety improvements that have benefitted all of us.