Companies like Uber, Lyft and TaskRabbit are examples of the so-called sharing economy, where technology matches people who need a service with people willing to work to perform the service. The technology company keeps a portion of the fee as a commission, with the rest going to the worker.

Sharing economy services have become increasingly popular, with many people earning a living from these companies. But the companies consider the workers to be independent contractors, arguing that many worker protections don’t apply to them, in particular access to workers’ compensation benefits.

Some people earn their entire living in the sharing economy, while others use it to supplement their income. For instance, according to the digital marketing site DMR:

![]() Uber has more than 8 million users.

Uber has more than 8 million users.

![]() 160,000 people driver for Uber, with more than 50,000 drivers added monthly.

160,000 people driver for Uber, with more than 50,000 drivers added monthly.

Uber is in nearly 300 U.S. cities.

Uber is in nearly 300 U.S. cities.

The average number of daily trips on Uber is 1 million.

The average number of daily trips on Uber is 1 million.

![]() There were 140 million Uber rides in 2014 alone.

There were 140 million Uber rides in 2014 alone.

About half of Uber drivers drive less than 15 hours per week.

About half of Uber drivers drive less than 15 hours per week.

![]() Half of Uber drivers did not drive to make money before Uber.

Half of Uber drivers did not drive to make money before Uber.

Are Sharing Economy Workers Employees or Independent Contractors?

With more and more Millennials becoming a part of the sharing economy they created, questions about how to reformulate worker programs, including health insurance, sick and vacation time and workers’ compensation, have come to the fore.

With more and more Millennials becoming a part of the sharing economy they created, questions about how to reformulate worker programs, including health insurance, sick and vacation time and workers’ compensation, have come to the fore.

Typically, workers in the sharing economy are considered independent contractors and can’t access workers’ compensation, which protects workers and provides benefits when they have been hurt on the job.

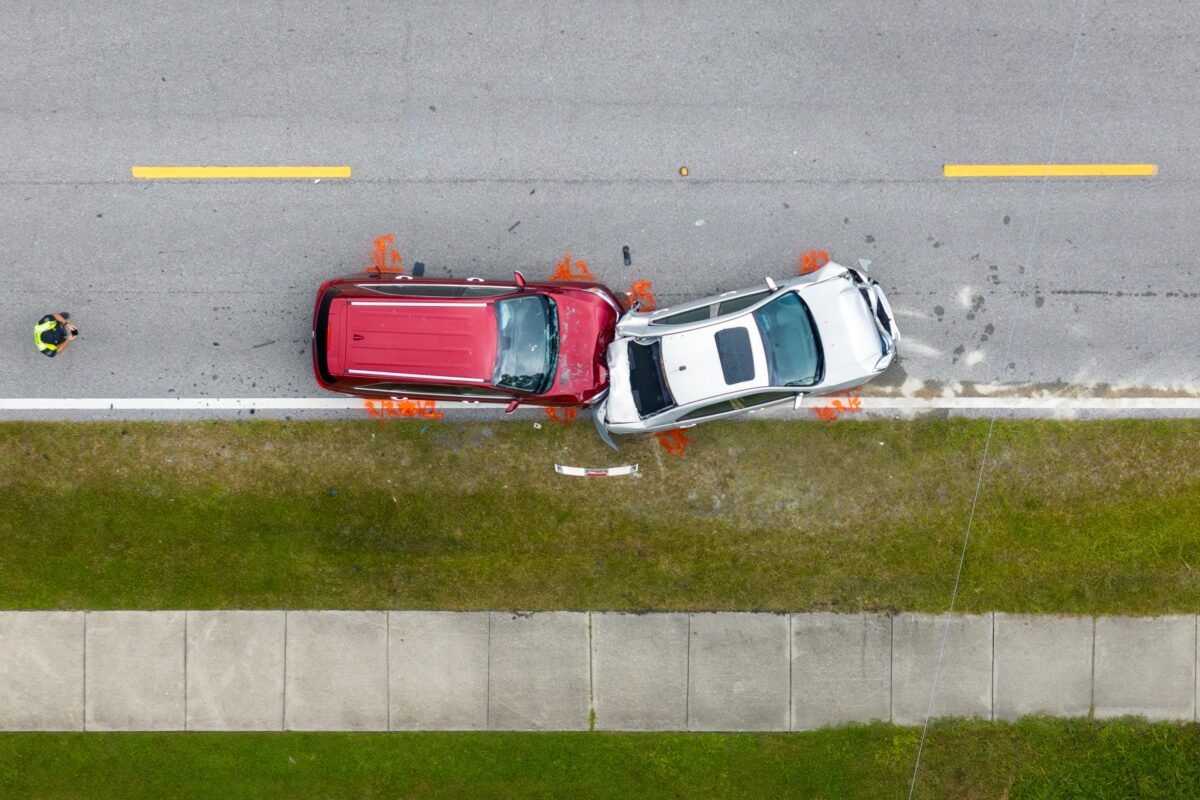

Some of these workers have been hurt while earning money for themselves and Uber.

Examples include drivers in Boston, Los Angeles and San Francisco who have been injured or assaulted by passengers. One Los Angeles Uber driver named Omar had his jaw broken in two places when a passenger hit him with a shiny object, as detailed in a Forbes article.

Examples include drivers in Boston, Los Angeles and San Francisco who have been injured or assaulted by passengers. One Los Angeles Uber driver named Omar had his jaw broken in two places when a passenger hit him with a shiny object, as detailed in a Forbes article.

Omar, who did not have health insurance, underwent surgery and was in the hospital for a week. But Uber considered itself to be under no obligation to help him with his medical bills or provide workers’ compensation benefits.

Omar, who did not have health insurance, underwent surgery and was in the hospital for a week. But Uber considered itself to be under no obligation to help him with his medical bills or provide workers’ compensation benefits.

“Unlike employees, independent contractors are largely free to set their own hours, pick their own clients and control other aspects of their work,” the Forbes article states. “In exchange, if they get hurt while working, whatever the reason, they’re on their own. Some sharing-economy workers are experienced freelancers, but many — like Omar — have never before relied on contract work for their full-time income, and they may not realize the full stakes of the tradeoff.”

The article also stated Omar may have good reasons to think Uber should pay for his injuries. While most taxi drivers in the United States are also considered independent contractors, they also are eligible for workers’ compensation in many places.

The article also stated Omar may have good reasons to think Uber should pay for his injuries. While most taxi drivers in the United States are also considered independent contractors, they also are eligible for workers’ compensation in many places.

In addition, driving as a profession has always had risks for violence. While apps eliminate the handling of cash, other risks remain, such as working alone, serving people who have been drinking and working at night and in unsafe neighborhoods. Federal statistics indicate drivers are 21 to 33 times more likely to be killed as compared to other workers, according to the article.

Companies worry that providing workers’ compensation coverage to shared economy workers could make them look more like employees, which could affect lawsuits from some of these workers who have said they are misclassified as contractors and are in fact employees, the Forbes article stated.

And while workers’ compensation could actually protect companies such as Uber – when injuries are covered by workers’ comp, the worker usually can’t sue the company for additional damages – it poses challenges in other areas. For instance, workers’ compensation is meant to replace wages, which would be difficult to determine for contractors who set their own hours, particularly if they work for more than one service.

“There are parts of workers’ compensation that these companies could take on,” Denise Cheng said in the Forbes article. She is an MIT affiliate researcher whose thesis focuses on labor in the sharing economy. “It could parallel or mirror a lot of what workers’ compensation looks like on a legal basis. But it might not make sense to call it workers’ comp.”

“There are parts of workers’ compensation that these companies could take on,” Denise Cheng said in the Forbes article. She is an MIT affiliate researcher whose thesis focuses on labor in the sharing economy. “It could parallel or mirror a lot of what workers’ compensation looks like on a legal basis. But it might not make sense to call it workers’ comp.”

Courts Struggle to Categorize Sharing Economy Workers

The workers’ compensation issue is one part of the question on how to classify those who work in the shared economy, and how to determine worker benefits in the future. Several independent contractors have filed suit.

The workers’ compensation issue is one part of the question on how to classify those who work in the shared economy, and how to determine worker benefits in the future. Several independent contractors have filed suit.

Uber is appealing a court ruling that a San Francisco-based driver is an employee, rather than an independent contractor, and is eligible for reimbursement of expenses, according to Insurance Journal.

Uber is appealing a court ruling that a San Francisco-based driver is an employee, rather than an independent contractor, and is eligible for reimbursement of expenses, according to Insurance Journal.

Insurance Journal also reported how in a ruling that a class-action lawsuit against Lyft should go to trial, U.S. District Court Judge Vince Chhabria wrote: “At first glance, Lyft drivers don’t seem much like employees. … But Lyft drivers don’t seem much like independent contractors either.”

The Insurance Journal article discussed a suggestion from Arun Sundararajan, a New York University professor who has researched the sharing economy, made in Financial Times: Separate benefits like health coverage and workers’ compensation from full-time employment.

“Another that’s been getting renewed attention lately would be to add a new legal class of worker somewhere between the employee and the independent contractor — the ‘dependent contractor,’” the Insurance Journal article stated.

In the Forbes article, Peers executive director Shelby Clark indicated something similar, suggesting more and more workers will need to get their benefits outside of traditional jobs as work and benefits will separate, just like pensions have in many cases.

If you have been injured in South Carolina while working for a sharing economy company such as Lyft, Uber or TaskRabbit, you should consult with an experienced workplace injury attorney to explore your potential options for recovering compensation.

If you have been injured in South Carolina while working for a sharing economy company such as Lyft, Uber or TaskRabbit, you should consult with an experienced workplace injury attorney to explore your potential options for recovering compensation.

Sources:

- DMR – By the Numbers 22 Amazing Uber Statistics

- MIT – Reading Between the Lines: Blueprints for a Worker Support Infrastructure in the Peer Economy

- Forbes – What Happens To Uber Drivers And Other Sharing Economy Workers Injured On The Job?

- Insurance Journal – Commission Rules Uber Drivers Employees, Not Contractors

- Insurance Journal – New Worker Classification Needed for Sharing Economy, Uber Drivers